|

|

| (12 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) |

| Line 1: |

Line 1: |

| __NOTOC__{{C604 pub

| | {{NC C604 Page |

| | image = Cir604.png

| | |sub_disc={{C604_pub/cover}} |

| | series = Circular 604

| |

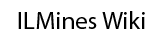

| | title = Mines in the Illinois Portion of the Illinois-Kentucky Fluorspar District

| |

| | part =

| |

| | chapter =

| |

| | frompg =

| |

| | topg =

| |

| | author = F. Brett Denny, W. John Nelson, Jeremy R. Breeden, and Ross C. Lillie

| |

| | date = 2020

| |

| | link = https://isgs.illinois.edu/publications/c604

| |

| | pdf = http://library.isgs.illinois.edu/Pubs/pdfs/circulars/c604.pdf

| |

| | store = http://library.isgs.illinois.edu/Pubs/pdfs/circulars/c604_fluorspar_district_map.pdf

| |

| | isbn =

| |

| | fromsor = Page Source

| |

| }} | |

| [[File:Cir604.png|frameless|left]]

| |

| == Mines in the Illinois Portion of the Illinois-Kentucky Fluorspar District == | | == Mines in the Illinois Portion of the Illinois-Kentucky Fluorspar District == |

| <big>'''F. Brett Denny,<sup>1</sup> W. John Nelson,<sup>1</sup> Jeremy R. Breeden,<sup>1</sup> and Ross C. Lillie<sup>2</sup><br>'''</big> | | <big>'''F. Brett Denny,<sup>1</sup> W. John Nelson,<sup>1</sup> Jeremy R. Breeden,<sup>1</sup> and Ross C. Lillie<sup>2</sup><br>'''</big> |

| Line 23: |

Line 8: |

| '''Suggested citation:<br>''' | | '''Suggested citation:<br>''' |

| Denny, F.B., W.J. Nelson, J.R. Breeden, and R.C. Lillie, 2020, Mines in the Illinois portion of the Illinois-Kentucky Fluorspar District: Illinois State Geological Survey, Circular 604, 73 p. and map. | | Denny, F.B., W.J. Nelson, J.R. Breeden, and R.C. Lillie, 2020, Mines in the Illinois portion of the Illinois-Kentucky Fluorspar District: Illinois State Geological Survey, Circular 604, 73 p. and map. |

| | | == Abstract == |

| === Abstract ===

| |

| This report compiles into a cohesive document details of the individual mines within the Illinois portion of the Illinois-Kentucky Fluorspar District (IKFD). This document also contains brief sections concerning the mining methods, geology, historical production figures, and theories of the origin of the ore deposits. In 2012, the Kentucky Geological Survey produced a map of the IKFD that covers only the Kentucky portion. The mine location map that accompanies this document was designed to augment the Kentucky fluorspar mine map. During research activities for this project, we gained access to confidential unpublished files from several mining companies. Maps, exploration reports, drill logs, and production figures were scanned and are available upon request at the Prairie Research Institute. Although the last mines in Illinois ceased operations in 1995, there is potential for future mining activities in deeper, relatively unexplored strata. The authors hope this report and the scanned documents will be helpful for future exploration activities and to other interested parties. | | This report compiles into a cohesive document details of the individual mines within the Illinois portion of the Illinois-Kentucky Fluorspar District (IKFD). This document also contains brief sections concerning the mining methods, geology, historical production figures, and theories of the origin of the ore deposits. In 2012, the Kentucky Geological Survey produced a map of the IKFD that covers only the Kentucky portion. The mine location map that accompanies this document was designed to augment the Kentucky fluorspar mine map. During research activities for this project, we gained access to confidential unpublished files from several mining companies. Maps, exploration reports, drill logs, and production figures were scanned and are available upon request at the Prairie Research Institute. Although the last mines in Illinois ceased operations in 1995, there is potential for future mining activities in deeper, relatively unexplored strata. The authors hope this report and the scanned documents will be helpful for future exploration activities and to other interested parties. |

| === Introduction ===

| | == Introduction == |

| The Illinois-Kentucky Fluorspar District (IKFD) was, for most of the 20th century, the primary source of fluorspar for the United States. The strategic importance of fluorspar was heightened during World War II because of the use of fluorspar in steel manufacturing. Production of fluorspar ore in this region peaked shortly after World War II and was sustained until the 1970s, when competition from foreign suppliers began to erode the dominance of this mineral district. The early mines were originally operated by dozens of local entrepreneurs producing small tonnages of fluorspar, but in the 1930s, corporate ventures such as Ozark-Mahoning and the Aluminum Ore Company (a precursor of ALCOA) entered the picture. The larger companies erected modern processing mills that allowed a lower grade ore to be enriched into a commercial product. Historical photographs of mines and mining activities in this district provide a nice pictorial archive of these mines and are compiled in the book Fluorspar Mining: Photos from Illinois and Kentucky, 1905–1995<ref>Russell, H.K., 2019, Fluorspar mining: Photos from Illinois and Kentucky, 1905–1995: Carbondale, Southern Illinois University Press, 84 p.</ref>. | | The Illinois-Kentucky Fluorspar District (IKFD) was, for most of the 20th century, the primary source of fluorspar for the United States. The strategic importance of fluorspar was heightened during World War II because of the use of fluorspar in steel manufacturing. Production of fluorspar ore in this region peaked shortly after World War II and was sustained until the 1970s, when competition from foreign suppliers began to erode the dominance of this mineral district. The early mines were originally operated by dozens of local entrepreneurs producing small tonnages of fluorspar, but in the 1930s, corporate ventures such as Ozark-Mahoning and the Aluminum Ore Company (a precursor of ALCOA) entered the picture. The larger companies erected modern processing mills that allowed a lower grade ore to be enriched into a commercial product. Historical photographs of mines and mining activities in this district provide a nice pictorial archive of these mines and are compiled in the book Fluorspar Mining: Photos from Illinois and Kentucky, 1905–1995(Russell 2019). |

|

| |

|

| “Fluorspar” is an industrial synonym for the mineral fluorite. The chemical formula for the mineral is calcium difluoride (CaF<sub>2</sub>). The fluorspar ore found in the IKFD is usually not 100% CaF<sub>2</sub> and contains minor impurities, mainly calcite and quartz. The ore may also contain galena, barite, and sphalerite, which can be separated and sold. For much of the 19th century, mining concentrated on galena, and fluorite was considered a waste product<ref>Goldstein, A., and D.A. Williams, 2008, The history of the Illinois-Kentucky Fluorite District, in F.B. Denny, A. Goldstein, J.A. Devera, D.A. Williams, Z. Lasemi, and W.J. Nelson, The Illinois-Kentucky Fluorite District, Hicks Dome, and Garden of the Gods in southeastern Illinois and northwestern Kentucky, in A.H. Maria and R.C. Counts, eds., From the Cincinnati Arch to the Illinois Basin: Geological field excursions along the Ohio River Valley: Geological Society of America, Field Guide 12, p. 18–20.</ref>. By the late 1800s, fluorspar was being utilized as a fluxing agent in the smelting of steel, which made fluorspar a valuable commodity. From 1914 to 1915, the ores of the IKFD accounted for more than 99% of fluorspar production in the United States<ref>Weller, S., C. Butts, L.W. Currier, and R.D. Salisbury, 1920, The geology of Hardin County and the adjoining part of Pope County: Illinois State Geological Survey, Bulletin 41, 416 p.</ref>. In about 1953 to 1954, the major use of fluorspar shifted from predominantly steel manufacturing to the manufacturing of hydrofluoric acid for the chemical and aluminum industries<ref>Voskuil, W.H., and W.L. Bush, 1955, Mineral production in Illinois in 1954: Illinois State Geological Survey, Circular 206, 59 p.</ref>. The primary uses of fluorspar today include the production of hydrofluoric acid and various other chemicals, steel manufacturing, aluminum smelting, hydrofluorocarbon, and fluoropolymer production<ref>McRae, M.E., 2016, Fluorspar [advance release], in Minerals yearbook 2014: U.S. Department of the Interior, U.S. Geological Survey, p. 26.1–26.10.</ref>. | | “Fluorspar” is an industrial synonym for the mineral fluorite. The chemical formula for the mineral is calcium difluoride (CaF<sub>2</sub>). The fluorspar ore found in the IKFD is usually not 100% CaF<sub>2</sub> and contains minor impurities, mainly calcite and quartz. The ore may also contain galena, barite, and sphalerite, which can be separated and sold. For much of the 19th century, mining concentrated on galena, and fluorite was considered a waste product (Goldstein and Williams 2008). By the late 1800s, fluorspar was being utilized as a fluxing agent in the smelting of steel, which made fluorspar a valuable commodity. From 1914 to 1915, the ores of the IKFD accounted for more than 99% of fluorspar production in the United States (Weller et al. 1920).. In about 1953 to 1954, the major use of fluorspar shifted from predominantly steel manufacturing to the manufacturing of hydrofluoric acid for the chemical and aluminum industries (Voskuil and Bush 1955). The primary uses of fluorspar today include the production of hydrofluoric acid and various other chemicals, steel manufacturing, aluminum smelting, hydrofluorocarbon, and fluoropolymer production (McRae 2016). |

| | {{C604_pub/navigation}} |

| | }} |

| | {{NC Data Subdistrict |

| | |figures=No |

| | }} |

| | ==References== |

|

| |

|

| === Production History === | | {{NC Subdistrict ref |

| Statistics on fluorspar and metal mining in Illinois from 1925 through 1985 are available in the Illinois Department of Natural Resources ''Illinois Coal Reports''. Published annually, the Illinois Coal Reports document the short tons of raw or crude ore mined in Illinois by company. The crude ore mined is milled or refined before being sold; therefore, the crude ore figures are larger than the finished or refined tonnage of fluorspar shipped. The refined or finished tonnage of fluorspar is reported in the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) ''Minerals Yearbooks''.

| | |bibliography=Goldstein, A., and D.A. Williams, 2008, The history of the Illinois-Kentucky Fluorite District, in F.B. Denny, A. Goldstein, J.A. Devera, D.A. Williams, Z. Lasemi, and W.J. Nelson, The Illinois-Kentucky Fluorite District, Hicks Dome, and Garden of the Gods in southeastern Illinois and northwestern Kentucky, in A.H. Maria and R.C. Counts, eds., From the Cincinnati Arch to the Illinois Basin: Geological field excursions along the Ohio River Valley: Geological Society of America, Field Guide 12, p. 18–20. |

| | | |source_loc=No |

| Available supply, demand, and economic conditions controlled the volume and sale price of fluorspar. The need for fluorspar increased during World Wars I and II and lessened during economic downturns, such as the Great Depression of the 1930s ([[:File:C604_figure_001.jpg|Figure 1a]]). From 1925 to 1985, more than 125 individual companies produced fluorspar in Illinois, but the top 24 companies accounted for 97% of the total crude ore production in Illinois (Table 1). Changing ownership of mines and properties makes tracking fluorspar production by company difficult; thus, Table 1 provides only an estimate of raw fluorspar production. An asterisk in Table 1 indicates a discrepancy or error in the data related to that company. This could be due to typographical errors, erroneous data submitted by the mining company, or other human errors. Although the data have a few problems, the ''Illinois Coal Reports'' as a whole are an excellent source of raw production figures for the Illinois portion of the district.

| | }} |

| <center>

| | {{NC Subdistrict ref |

| {| class="wikitable" style="text-align: center;"

| | |bibliography=McRae, M.E., 2016, Fluorspar [advance release], in Minerals yearbook 2014: U.S. Department of the Interior, U.S. Geological Survey, p. 26.1–26.10. |

| |-

| | |source_loc=No |

| |<gallery caption="" widths=250px heights=250px perrow=4>

| | }} |

| C604 figure 001.jpg|'''Figure 1'''

| | {{NC Subdistrict ref |

| </gallery>

| | |bibliography=Russell, H.K., 2019, Fluorspar mining: Photos from Illinois and Kentucky, 1905–1995: Carbondale, Southern Illinois University Press, 84 p. |

| |}

| | |source_loc=No |

| {| class="wikitable"

| | }} |

| |-

| | {{NC Subdistrict ref |

| ! colspan="3" | Table 1 Production of “raw” crude ore in Illinois by company from 1925 to 1995.<sup>1</sup>

| | |bibliography=Voskuil, W.H., and W.L. Bush, 1955, Mineral production in Illinois in 1954: Illinois State Geological Survey, Circular 206, 59 p. |

| |- style="font-weight:bold;"

| | |source_loc=No |

| | Company

| | }} |

| | Raw (short tons)

| | {{NC Subdistrict ref |

| | Years of production

| | |bibliography=Weller, S., C. Butts, L.W. Currier, and R.D. Salisbury, 1920, The geology of Hardin County and the adjoining part of Pope County: Illinois State Geological Survey, Bulletin 41, 416 p. |

| |-

| | |source_loc=No |

| | Ozark-Mahoning (OZM) and related *

| | }} |

| | style="text-align:right;" | 10,239,405

| |

| | style="text-align:center;" | 1938-1995 | |

| |-

| |

| | Minerva Oil Company, Inverness Mining Company, and Allied Chemical Company*

| |

| | style="text-align:right;" | 5,021,463

| |

| | style="text-align:center;" | 1944-1982

| |

| |-

| |

| | Aluminum Ore Company (ALCOA) and related

| |

| | style="text-align:right;" | 1,994,109 | |

| | style="text-align:center;" | 1936-1965

| |

| |-

| |

| | Rosiclare Lead and Fluorspar Company*

| |

| | style="text-align:right;" | 1,990,745

| |

| | style="text-align:center;" | 1925-1952

| |

| |-

| |

| | Crystal Fluorspar Company

| |

| | style="text-align:right;" | 411,799

| |

| | style="text-align:center;" | 1930-1951

| |

| |-

| |

| | Hillside Mines

| |

| | style="text-align:right;" | 310,231

| |

| | style="text-align:center;" | 1925-1954

| |

| |-

| |

| | Illinois Minerals*

| |

| | style="text-align:right;" | 190,704

| |

| | style="text-align:center;" | 1977-1979

| |

| |-

| |

| | Benzon

| |

| | style="text-align:right;" | 163,989

| |

| | style="text-align:center;" | 1925-1937

| |

| |-

| |

| | Goose Creek Mining Company

| |

| | style="text-align:right;" | 149,839

| |

| | style="text-align:center;" | 1952-1958

| |

| |-

| |

| | Victory Fluorspar Mining Company

| |

| | style="text-align:right;" | 138,281

| |

| | style="text-align:center;" | 1929-1945; 1952-1955

| |

| |-

| |

| | Hoeb Mining Company

| |

| | style="text-align:right;" | 87,610

| |

| | style="text-align:center;" | 1956-1963

| |

| |-

| |

| | G.B. Mining*

| |

| | style="text-align:right;" | 70,298

| |

| | style="text-align:center;" | 1948-1949

| |

| |-

| |

| | Patton and Sons

| |

| | style="text-align:right;" | 60,356

| |

| | style="text-align:center;" | 1956-1967

| |

| |-

| |

| | Fluorspar Products

| |

| | style="text-align:right;" | 60,078

| |

| | style="text-align:center;" | 1934-1947

| |

| |-

| |

| | A.H. Stacey

| |

| | style="text-align:right;" | 53,213

| |

| | style="text-align:center;" | 1946-1951

| |

| |-

| |

| | P.M.T. Mining

| |

| | style="text-align:right;" | 43,444 | |

| | style="text-align:center;" | 1949-1956

| |

| |-

| |

| | Hastie Mining*

| |

| | style="text-align:right;" | 41,650 | |

| | style="text-align:center;" | 1969; 1973-present

| |

| |-

| |

| | Mackey-Humm

| |

| | style="text-align:right;" | 40,088

| |

| | style="text-align:center;" | 1953-1956

| |

| |-

| |

| | Inland Steel

| |

| | style="text-align:right;" | 34,363

| |

| | style="text-align:center;" | 1945-1948

| |

| |-

| |

| | Knight, Knight, and Clark

| |

| | style="text-align:right;" | 23,650

| |

| | style="text-align:center;" | 1926-1938

| |

| |-

| |

| | Crown Fluorspar Company

| |

| | style="text-align:right;" | 23,021

| |

| | style="text-align:center;" | 1942

| |

| |-

| |

| | Yingling Oil Company*

| |

| | style="text-align:right;" | 21,557

| |

| | style="text-align:center;" | 1942-1948; 1951

| |

| |-

| |

| | colspan="3" | | |

| |-

| |

| | style="font-weight:bold;" | Total top producers

| |

| | style="text-align:right;" | '''21,169,893'''

| |

| |

| |

| |-

| |

| | style="font-weight:bold;" | Other producers

| |

| | style="text-align:right;" | '''652,471'''

| |

| |

| |

| |- style="font-weight:bold;"

| |

| | Estimated total raw short tons | |

| | style="text-align:right;" | '''21,822,364'''

| |

| | style="font-weight:normal;" |

| |

| |-

| |

| | colspan="3" | <sup>1</sup>Data extracted from Illinois Coal Reports and other sources. An asterisk (*) denotes a probable discrepancy in the data (see text for details).

| |

| |}</center>

| |

| | |

| The ''Illinois Coal Reports'' indicate that in 1925, seven companies were mining fluorspar in Illinois. In 1936, eleven companies reported production, and in 1941, twenty-nine companies were producing fluorspar ore. In 1946, twenty-three companies reported production. The number of companies producing ore in Illinois in 1955 decreased to ten, and by 1965, only five companies were producing ore. During the late 1970s, IKFD reserves and production continued to decline. The decline was also partly affected by competition from imported fluorspar from Mexico, China, and South Africa. In 1981, the Hastie Mining Company produced 2,404 tons of crude ore, the Inverness Mining Company produced 128,085 tons of crude ore at its Minerva Mine and 46,105 tons of crude ore at its Spivey Mine, and Ozark-Mahoning produced a combined total of 199,506 tons from several mines.

| |

| | |

| The single largest producer in the IKFD was [[Ozark-Mahoning_Company|Ozark-Mahoning]] and related companies. Ozark Mining began an exploration program in southern Illinois in 1937 and erected a mill in Rosiclare in 1939. In 1946, the Mahoning Mining Company and Ozark Chemical Company merged to form the Ozark-Mahoning Company<ref>Evans, V.A., and D.L. Hellier, 1986, Case study: [[Ozark-Mahoning_Company|Ozark-Mahoning]], sole surviving US fluorspar producer: Englewood, Colorado, Society for Mining, Metallurgy and Exploration, 3 p.</ref>. Ozark-Mahoning was acquired by Pennwalt in 1974 and operated as a subsidiary. Elf Atochem acquired Pennwalt in 1990, and Elf Atochem merged with Total Fina in 1999. This company was referred to as [[Ozark-Mahoning_Company|Ozark-Mahoning]] or simply Mahoning, even after the purchases and mergers. Ozark-Mahoning company files indicate the company produced more than 10 million tons of raw crude ore. The raw production estimate for Ozark-Mahoning in Table 1 has been supplemented by information contained in [[Ozark-Mahoning_Company|Ozark-Mahoning]] company scanned documents.

| |

| | |

| By comparing the raw tons in the ''Illinois Coal Reports'' with the refined and shipped tons in the USGS ''Minerals Yearbooks'', we can estimate the average grade of the ore by year ([[:File:C604_figure_001.jpg|Figure 1b]]). When compiling this publication, we noticed a few obvious errors in the statistics provided in the Illinois Coal Reports or USGS Minerals Yearbooks. In 1925 and 1932, the USGS ''Minerals Yearbooks'' reported more finished tons shipped than the ''Illinois Coal Reports'' reported raw tons being mined, which skews the ore grade above 100%. The ''Illinois Coal Reports'' cite no production for the S.C. Yingling Company in 1941, 809,857 raw tons in 1942, and 2,190 raw tons in 1943. The 1942 Yingling production of 800,000 tons far exceeds maximum annual output of the Rosiclare Mine, which Weller<ref>Weller, J.M., 1943f, Illinois fluorspar investigations, I. Rosiclare district, D. Rosiclare Mine and vicinity: Illinois State Geological Survey, unpublished manuscript, J.M. Weller, ms. 11-D, 19 handwritten pages and 3 pls.</ref> identified as the largest fluorspar mine in the United States. We suggest Yingling produced significantly less than 800,000 tons. Except for 1942, Yingling never produced more than 8,000 raw tons. Subtraction of the anomalous production of Yingling in 1942 allows an average ore grade to fall more in line with the historical fluorspar grade during that time ([[:File:C604_figure_001.jpg|Figure 1b]]). In 1976, the ''Illinois Coal Reports'' state that 189,975 tons was mined by Hastie Mining Company. In 1975, Hastie reported 4,591 raw tons, whereas in 1977, Hastie reported 1,751 raw tons. A conversation with Don Hastie, owner of Hastie Mining, indicated that Hastie Mining probably produced about 5,000 tons of spar during 1976 (Don Hastie, personal communication with Brett Denny, February 28, 2020). Illinois Minerals is listed as having produced fluorspar from 1977 to 1979. However, no corroborating information could be obtained concerning these mines. Eric Livingston, geologist with Ozark-Mahoning from the 1970s through the 1990s, could not remember any Illinois Minerals mining operations in southeastern Illinois (Eric Livingston, personal communication with Ross Lillie, March 2020). Illinois Minerals occupied an office in Alexander County, and amorphous silica (tripoli) production may be what was inaccurately reported as fluorspar production. The G.B. Mining Company also reported 69,745 tons of raw ore in 1949 but only 553 tons in 1948. These are the only 2 years of production from this company, and although the large tonnage produced in 1949 seems speculative, this tonnage is possible and is reported in Table 1.

| |

| | |

| In the late 1800s to early 1900s, only high-grade ore was mined, with little milling or processing being applied. The ore grade gradually decreased through time, partially because of the higher grade deposits being mined first. However, through time, as milling equipment and processing techniques improved, a lower grade ore could be mined profitably. Improved milling techniques allowed the concentration and enrichment of fluorspar as well as the concentration of secondary minerals such as lead, barite, and sphalerite, which could make a lower grade ore economic. Obviously, some mines contained higher grade material, and some lower grade ore was economic mainly because of secondary minerals. The USGS ''Minerals Yearbooks'' from 1925 to 1927 indicate an average ore grade of 50% to 60% CaF<sub>2</sub> during that time period.

| |

| | |

| === Geology of the Illinois-Kentucky Fluorspar District ===

| |

| | |

| === Mining Methods ===

| |

| | |

| === Mineral Subdistricts and Individual Mines ===

| |

| {{:Fluorspar_District}}

| |

| | |

| === References ===

| |

| <references />

| |

| {{#Set:Has parent page=Fluorspar}} | | {{#Set:Has parent page=Fluorspar}} |

| {{#css:

| |

| #ca-key1 { display:none!important; }

| |

| }}

| |

| Mines in the Illinois Portion of the Illinois-Kentucky Fluorspar District

|

|

| Series

|

Circular 604

|

| Author

|

F. Brett Denny, W. John Nelson, Jeremy R. Breeden, and Ross C. Lillie

|

| Date

|

2020

|

| Buy

|

Web page

|

| Report

|

PDF file

|

| Map

|

PDF file

|

Mines in the Illinois Portion of the Illinois-Kentucky Fluorspar District

F. Brett Denny,1 W. John Nelson,1 Jeremy R. Breeden,1 and Ross C. Lillie2

1Illinois State Geological Survey, Prairie Research Institute, University of Illinois, Champaign,Illinois

2North Star Minerals, Traverse City, Michigan

Suggested citation:

Denny, F.B., W.J. Nelson, J.R. Breeden, and R.C. Lillie, 2020, Mines in the Illinois portion of the Illinois-Kentucky Fluorspar District: Illinois State Geological Survey, Circular 604, 73 p. and map.

Abstract

This report compiles into a cohesive document details of the individual mines within the Illinois portion of the Illinois-Kentucky Fluorspar District (IKFD). This document also contains brief sections concerning the mining methods, geology, historical production figures, and theories of the origin of the ore deposits. In 2012, the Kentucky Geological Survey produced a map of the IKFD that covers only the Kentucky portion. The mine location map that accompanies this document was designed to augment the Kentucky fluorspar mine map. During research activities for this project, we gained access to confidential unpublished files from several mining companies. Maps, exploration reports, drill logs, and production figures were scanned and are available upon request at the Prairie Research Institute. Although the last mines in Illinois ceased operations in 1995, there is potential for future mining activities in deeper, relatively unexplored strata. The authors hope this report and the scanned documents will be helpful for future exploration activities and to other interested parties.

Introduction

The Illinois-Kentucky Fluorspar District (IKFD) was, for most of the 20th century, the primary source of fluorspar for the United States. The strategic importance of fluorspar was heightened during World War II because of the use of fluorspar in steel manufacturing. Production of fluorspar ore in this region peaked shortly after World War II and was sustained until the 1970s, when competition from foreign suppliers began to erode the dominance of this mineral district. The early mines were originally operated by dozens of local entrepreneurs producing small tonnages of fluorspar, but in the 1930s, corporate ventures such as Ozark-Mahoning and the Aluminum Ore Company (a precursor of ALCOA) entered the picture. The larger companies erected modern processing mills that allowed a lower grade ore to be enriched into a commercial product. Historical photographs of mines and mining activities in this district provide a nice pictorial archive of these mines and are compiled in the book Fluorspar Mining: Photos from Illinois and Kentucky, 1905–1995(Russell 2019).

“Fluorspar” is an industrial synonym for the mineral fluorite. The chemical formula for the mineral is calcium difluoride (CaF2). The fluorspar ore found in the IKFD is usually not 100% CaF2 and contains minor impurities, mainly calcite and quartz. The ore may also contain galena, barite, and sphalerite, which can be separated and sold. For much of the 19th century, mining concentrated on galena, and fluorite was considered a waste product (Goldstein and Williams 2008). By the late 1800s, fluorspar was being utilized as a fluxing agent in the smelting of steel, which made fluorspar a valuable commodity. From 1914 to 1915, the ores of the IKFD accounted for more than 99% of fluorspar production in the United States (Weller et al. 1920).. In about 1953 to 1954, the major use of fluorspar shifted from predominantly steel manufacturing to the manufacturing of hydrofluoric acid for the chemical and aluminum industries (Voskuil and Bush 1955). The primary uses of fluorspar today include the production of hydrofluoric acid and various other chemicals, steel manufacturing, aluminum smelting, hydrofluorocarbon, and fluoropolymer production (McRae 2016).

Continue Reading

Circular 604 | Production History | Geology of the Illinois-Kentucky Fluorspar District | Mining Methods | Mineral Subdistricts and Individual Mines | Conclusions and Acknowledgments

References

- Goldstein, A., and D.A. Williams, 2008, The history of the Illinois-Kentucky Fluorite District, in F.B. Denny, A. Goldstein, J.A. Devera, D.A. Williams, Z. Lasemi, and W.J. Nelson, The Illinois-Kentucky Fluorite District, Hicks Dome, and Garden of the Gods in southeastern Illinois and northwestern Kentucky, in A.H. Maria and R.C. Counts, eds., From the Cincinnati Arch to the Illinois Basin: Geological field excursions along the Ohio River Valley: Geological Society of America, Field Guide 12, p. 18–20.

|

- McRae, M.E., 2016, Fluorspar [advance release], in Minerals yearbook 2014: U.S. Department of the Interior, U.S. Geological Survey, p. 26.1–26.10.

|

- Russell, H.K., 2019, Fluorspar mining: Photos from Illinois and Kentucky, 1905–1995: Carbondale, Southern Illinois University Press, 84 p.

|

- Voskuil, W.H., and W.L. Bush, 1955, Mineral production in Illinois in 1954: Illinois State Geological Survey, Circular 206, 59 p.

|

- Weller, S., C. Butts, L.W. Currier, and R.D. Salisbury, 1920, The geology of Hardin County and the adjoining part of Pope County: Illinois State Geological Survey, Bulletin 41, 416 p.

|