Circular 530 Coal Balls

| Geologic Disturbances in Illinois Coal Seams | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Channels | Split Coal | Rolls | Limestone Bosses | Clay Dikes | White Top | Igneous Dikes | Joints | Coal Balls | Miscellaneous Disturbances | Acknowledgments |

Coal Balls

During the Pennsylvanian Period, layers of peat sometimes became saturated shortly after burial with water rich in dissolved minerals. Minerals permeated parts of the peat, turning them into stone before they could turn into coal. Such fossilized peat masses often have a spherical or lens shape; they are known as coal balls.

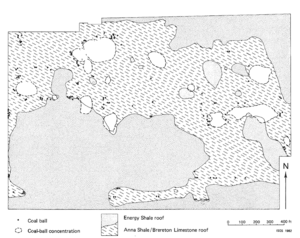

In the Illinois Basin Coal Field, coal balls have been reported in 17 different seams, including most minable seams (Phillips, Avcin, and Berggren, 1976). Most are overlain by black shale or limestone, formed from marine water deposits with a high mineral content. Apparently, the dissolved minerals precipitated to form coal balls. (Sulfur in seawater is also the source of much sulfur in coal [Gluskoter and Simon, 19681].) For example, coal balls at Old Ben Mine No. 24 are found only in coal overlain by or immediately adjacent to the marine, black fissile Anna Shale. Coal overlain by nonmarine Energy Shale contains almost no coal balls (fig. 37). Rarely do coal balls occur in coal topped by gray shale, siltstone, or sandstone, formed from lake or river deposits. The reason for this relationship is that freshwater contains a lower proportion of dissolved minerals than seawater. Also coal overlain by freshwater sediments was protected from later invasions of seawater. Mapping a t Old Ben Mine No. 24 illustrates the general rule that coal balls occur in coal overlain by marine strata (fig. 37).

Most coal balls are composed of calcium carbonate (CaC03) and varying amounts of pyrite (FeS2): calcareous coal balls are medium to dark gray or tawny brown; pyritic ones are golden, brassy, or greenish gray. Another type, composed of silica (Si02), is encountered less often: siliceous coal balls may be gray or black.

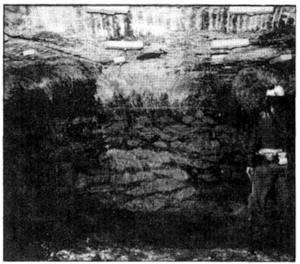

Coal balls commonly occur as isolated nodules or lenses scattered through the seam, especially in the upper layers. They may be several inches to several feet in diameter (fig. 38). Occasionally, large masses of coal balls are encountered. Entire seams may be mineralized in areas 100 feet in diameter or larger. The structure may vary from multiple zones of coal balls throughout the coal, to intergrown masses separated by thin stringers of coal, to huge masses of solid rock (fig. 39).

Paleobotanists are greatly interested in coal balls because many contain beautifully preserved remains of plants that grew in coal-forming swamps. In many cases the most minute details of plants, even their cellular structure can be observed microscopically. Such observation is not possible in ordinary coal because coalification destroys plant structure. Discoveries of coal balls should be reported to specialists in studies of coal balls and fossil plants; for instance, T. L. Phillips of the Botany Department at the University of Illinois. Further research may lead to development of techniques to predict the occurrence of mineralized peat before mining (DeMaris et al., 1983).

Mining problems.

Both calcareous and siliceous coal balls are extremely hard and dense compared to the surrounding coal; they easily damage drills, miner bits, crushers, and related equipment used in mining and preparation. Isolated coal balls are only a minor nuisance in mining. Massive coal balls are troublesome, even when encountered in surface mines. Generally loaders can bypass them, but sometimes they must be blasted out or graded over to allow passage of equipment.

In underground mines, massive coal balls are more serious. An example of an underground mine troubled by coal balls in one part of its field is Old Ben Mine No. 24 in the Herrin Coal of Franklin County. Concentrated masses of coal balls, some more than 100 feet in diameter, were struck in three panels laid out for longwall mining (fig. 37). Repeated damage to the shearer and stage loader (crusher) resulted from mining the large lenses of rock in the coal. Two masses of coal balls were so solidly intergrown that the shearer could not cut them, and the miners had to resort to drilling and blasting to clear out these deposits. The belt entry of one panel had to be relocated to bypass massive coal balls; and two of the three longwall panels were shortened to avoid longwall mining through them (Bauer and DeMaris, 1982).

At another mine in the Herrin Coal of east-central Illinois, extremely hard, black siliceous coal balls were found in areas of abnormally thin coal (apparently, because it had been partly eroded). Siliceous coal balls form intergrown masses or layers as much as 2 feet thick in the upper part of the seam. They are very difficult to cut with the continuous miner and must be left in the roof. Coal nearby is abnormally dull, hard, and high in ash. The banding in the coal is distorted and locally destroyed; it contains many lenses and bands of fusain (mineral charcoal or mother coal) and a high proportion of clay as thin lenses, layers, and finely disseminated particles. Probably, the peat was partly eroded, mixed with clay, oxidized somewhat, then mineralized with silica before it was coalified. The dull, disturbed coal is hard to mine and of little value as a fuel, even where it does not contain siliceous coal balls.

References

- Bauer, R. A., and P. J. DeMaris, 1982, Geologic investigation of roof and floor strata: longwall demonstration, Old Ben Mine No. 24, Final Technical Report: Part 1, U.S. DOE Contract ET-76-G- 01 -9007, lIllinois State Geological Survey Contract/Grant Report: 1982-2,49 p.

- Phillips, T. L., M. J. Avcin, and D. J. Berggren, 1976, Fossil peat from the lllinois Basin: lllinois State Geological Survey Educational Series 11, 39 p.